Science fiction writer William Gibson famously stated, “the future is already here. It’s just not very evenly distributed.” Past events in the history of technology bear this out: Doug Engelbart, for example, blew the world away in 1969 with his demonstration of a futuristic working prototype of hypertext, windows, the mouse, word processing, videoconferencing and more. It took another 30 or 40 years for the ideas Engelbart showed to a stunned 60s audience to become mainstream. Similar ahead-of-the-curve experiments took place with email, the German WW II V-2 rocket program, and semiconductors, among many other technical and scientific disciplines.

People “ahead of their time” is a common trope in Western culture. From Thomas Edison to Steve Jobs, certain people have been able to see farther than anyone else. In fact, Edison and Jobs share something remarkable: they were ecosystem builders. Edison, as important as perfecting the electric light bulb, also created an infrastructure for the bulb to live in—power plants, massive amounts of wiring – and he built his first power station on Pearl Street in NYC, right near his Wall Street investors. Jobs, with Apple’s series of “i” devices, defined a software ecosystem of digital content as important as the devices themselves.

This year we celebrate the 50th anniversary of a home computer built and operated more than a decade before ‘official’ home computers arrived on the scene. Yes, before the ‘trinity’ of the Apple II, the Commodore PET and the Radio Shack TRS-80–all introduced in 1977—Jim Sutherland, a quiet engineer and family man in Pittsburgh, was building a computer system on his own for his family. Sutherland configured this new computer system to control many aspects of his home with his wife and children as active users. It truly was a home computer—that is, the house itself was part of the computer and its use was integrated into the family’s daily routines.

Sutherland’s computer was called the ECHO IV – the Electronic Computing Home Operator.

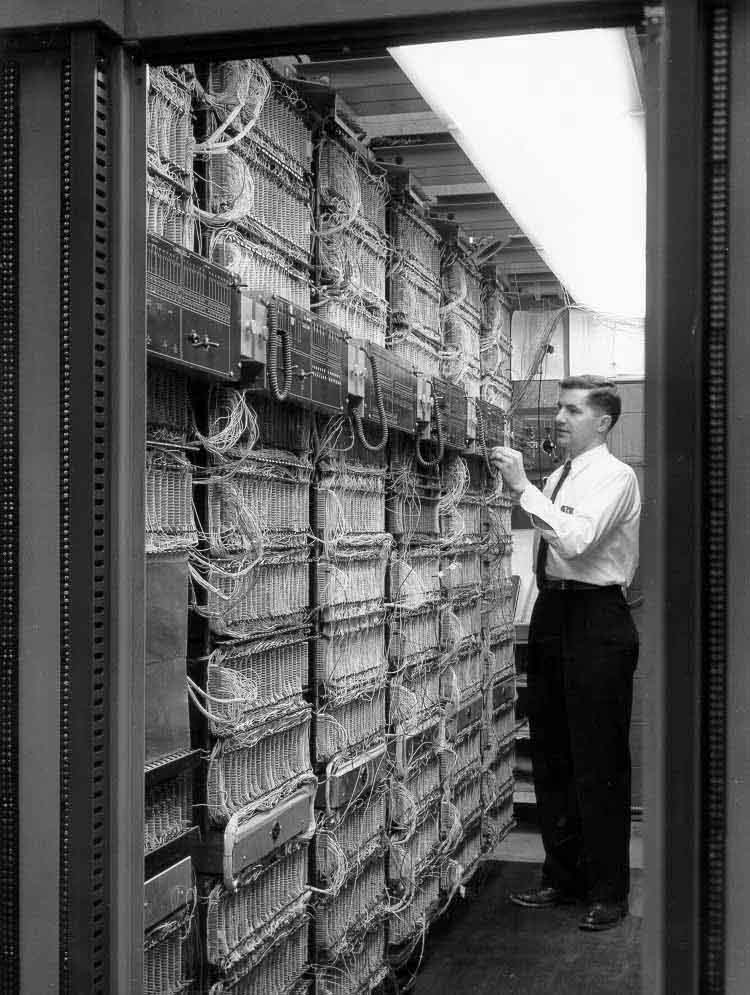

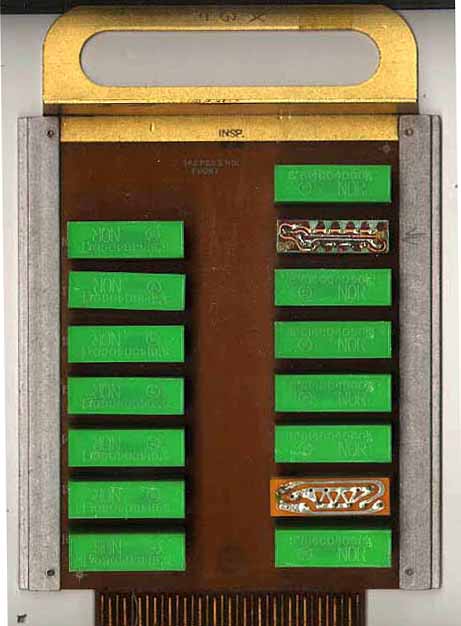

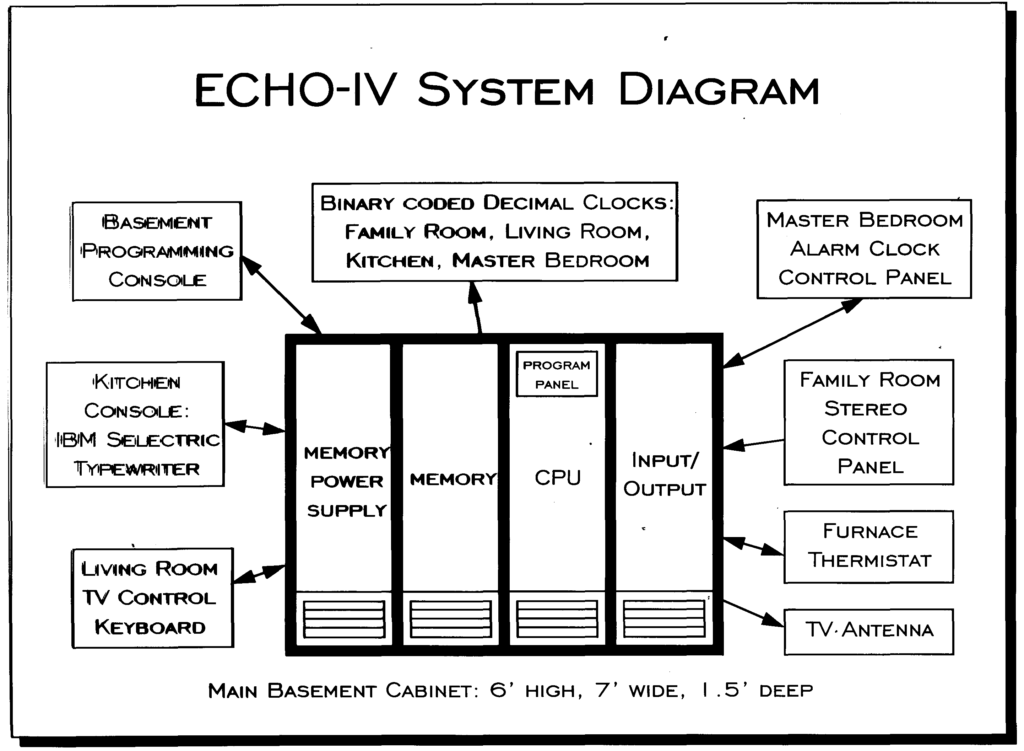

ECHO IV comprised four large (6’ x 2’ x 6’) cabinets weighing approximately 800 lbs and included a central processing unit (CPU) constructed from surplus circuit modules from a Westinghouse Prodac-IV industrial process control computer; magnetic core memory, I/O circuitry and power supplies. With the permission of his employer, Westinghouse, Sutherland took these modules home and designed and built the ECHO IV in less than a year.

Jim Sutherland inside a Westinghouse Prodac-IV industrial process control computer system.

Westinghouse Prodac-IV module.

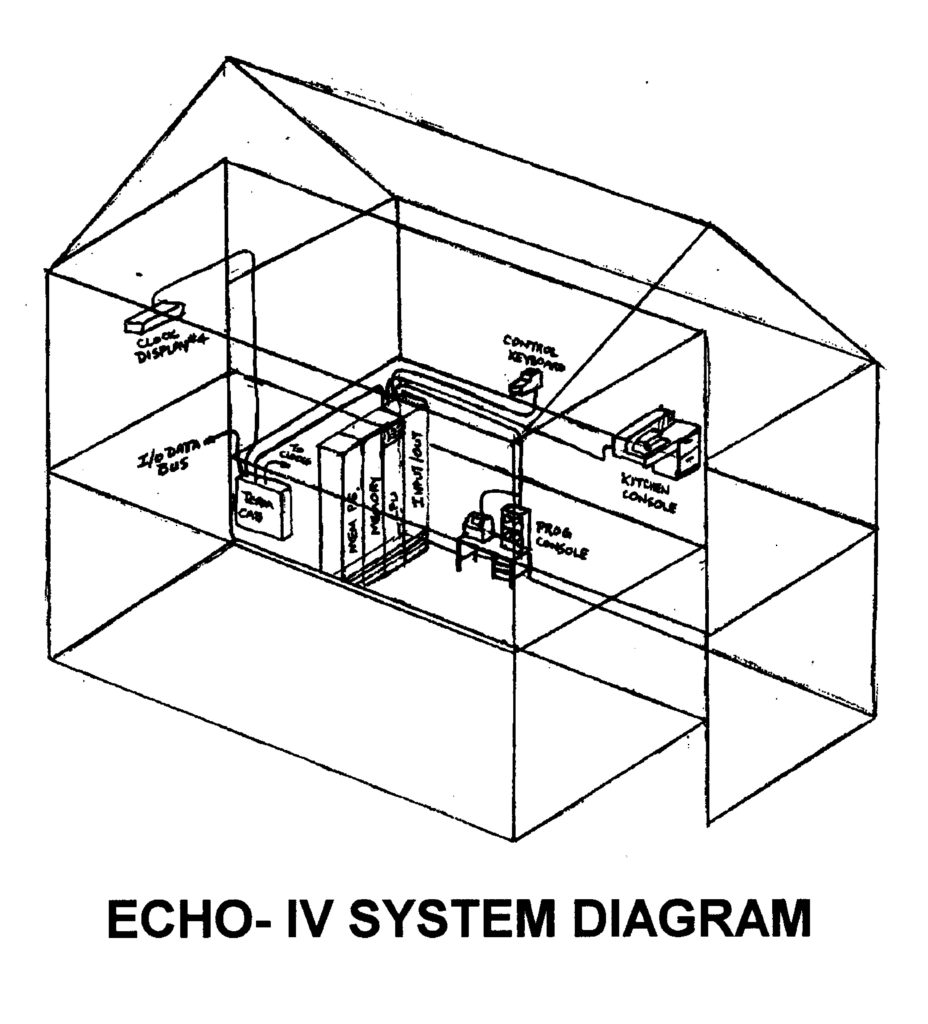

Several keypads and terminals around the house allowed for interaction by Mrs. Sutherland and the family’s three children. The system was operational on April 16, 1966.

Main ECHO IV system diagram.

Internal house wiring for the ECHO IV.

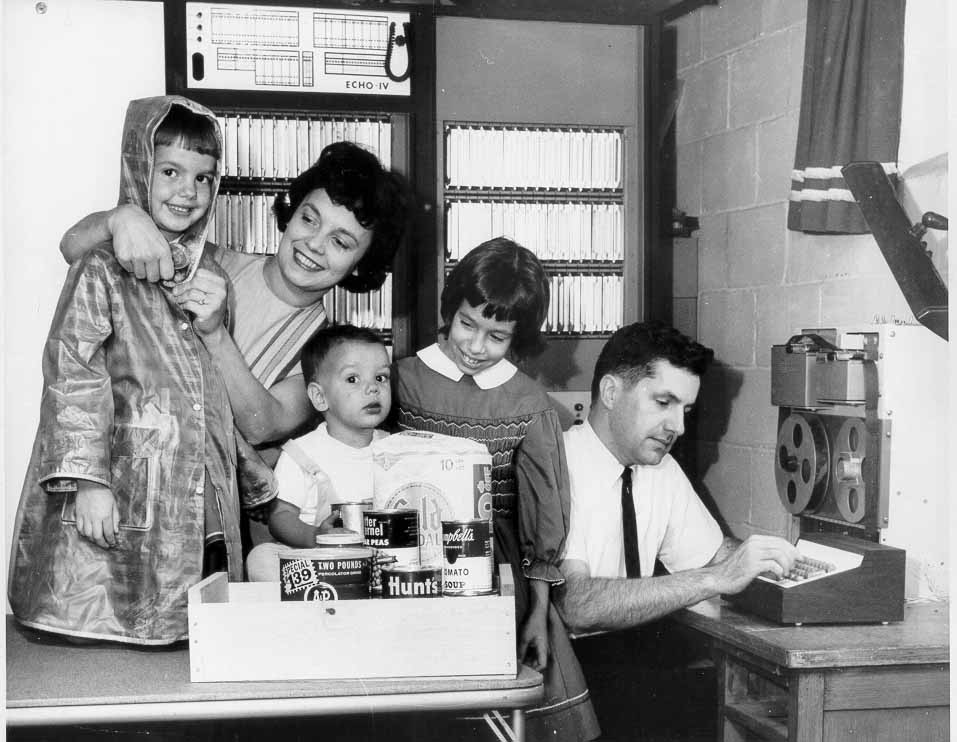

Jim Sutherland sits at the ECHO IV computer. His wife Ruth, puts a raincoat on daughter Sally, while Jay and Ann look on. (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 1966)

Programming and interacting with ECHO IV was accomplished by several means: front-panel switches on the main cabinet, a programmer’s keypad (for octal) near the main cabinet, a paper tape reader and punch, and the kitchen console, which was based on an IBM 735 Selectric typewriter and was used for word processing. This latter ability deserves a closer look. With ECHO IV, documents typed on the Selectric keyboard could be stored in ECHO IV’s memory, to be reprinted later. Formatting changes and page numbers could be automatically added to printed documents and, in 1975, ECHO IV was used to format a 516-page scholarly book on post-Revolutionary War land grant surveys. Here again is Gibson’s ‘unevenly distributed’ future – it would be decades before people would be doing word processing at home on their own computer.

ECHO IV caught the attention of the media fairly quickly, with dozens of publications covering it from its initial start-up in 1966 until the 1970s. Much of this coverage is ironic in tone, with playful nods to the sanctity of the domestic sphere and how a computer may interfere with traditional roles in the household. Because it is so evocative of the era, below are Ruth Sutherland’s thoughts on “Living with ECHO IV,” which I excerpt here in full:

IMPRESSIONS OF A HOMEMAKER WITH A COMPUTER IN HER BASEMENT

As part of Ruth Sutherland’s presentation, she also conducted a survey of conference attendees to gauge what people thought of computers in the home and how they might help them in their daily lives. Here are the results:

Some Home Computer Ideas from AHEA Conference – Dallas, TX

(Home Economics teachers’ responses to questionnaire – 1967)

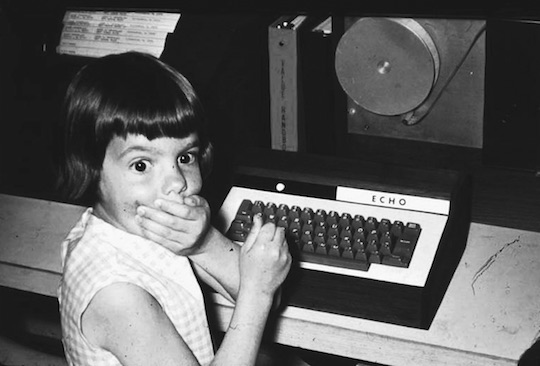

Sally Sutherland, immediately after turning ECHO-IV on by pressing a key. The system was usually in standby mode to save power.

These desiderata are fascinating and, except for the tasks requiring a robotic/android interface – tasks like taking out the trash or feeding a baby at night – they have almost all come to pass. What this shows is both the persistence of an unchanging domestic hierarchy of needs and the prescience of Jim Sutherland whose unique computer stimulated such thinking about the future role of a computer in the home. It’s important to calibrate our thinking about how large a leap this was for the people living in this era: having a computer in the home in 1965 was akin in most people’s minds to having a personal aircraft carrier or a home cyclotron. It took the technical ability and personal family motivation of Jim Sutherland to show us what might be coming, fifty years ago.

Donated by Jim Sutherland to the Computer History Museum in 1984. (CHM #X509.84)

Electronic Computer for Home Operation (ECHO): The First Home Computer, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 16, No. 3, 1994 pages 59 – 61.