The artist Lillian Schwartz was honored with a CHM Fellow award in 2021 for her pioneering work at the intersection of art and computing. In the first half of the 1970s, she created a remarkable series of films that brought the new technology of computer animation into the artworld. Her work, and those of artists like her, expanded the scope of media art, and spurred fresh developments in technology. Through a decades-long residency at Bell Labs, and collaborations at IBM and the MIT Media Lab, Schwartz continued to explore the possibilities of the computer for artistic exploration. Through teaching and writing, she shared what she had learned with others. Schwartz’s work has been exhibited widely and internationally at a variety of museums and galleries, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney. Several of her films from the 1970s are in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Her entire archive is now held by The Henry Ford.

Born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1927, Lillian Schwartz was the child of recent immigrants to the United States. Her father had come from Russia and her mother from England. Schwartz’s father worked as a barber, while her mother worked as the caregiver for the couple’s thirteen children.

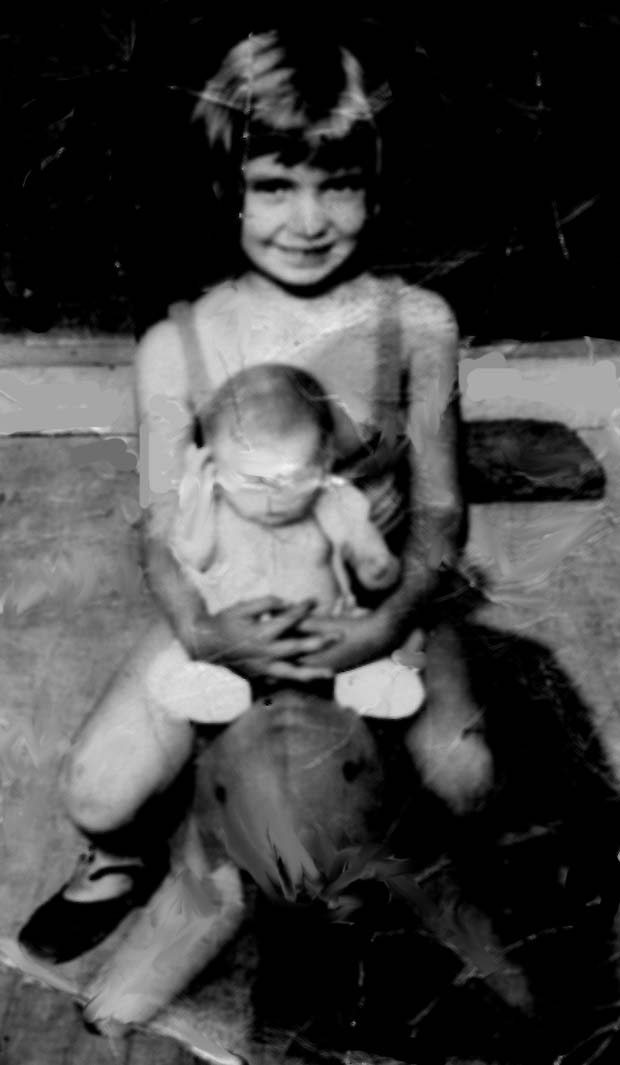

Lillian Schwartz c. 1930. Schwartz’s childhood coincided with the Great Depression of the 1930s. This, and her father’s ailing health, spelled significant economic challenges for the family. Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

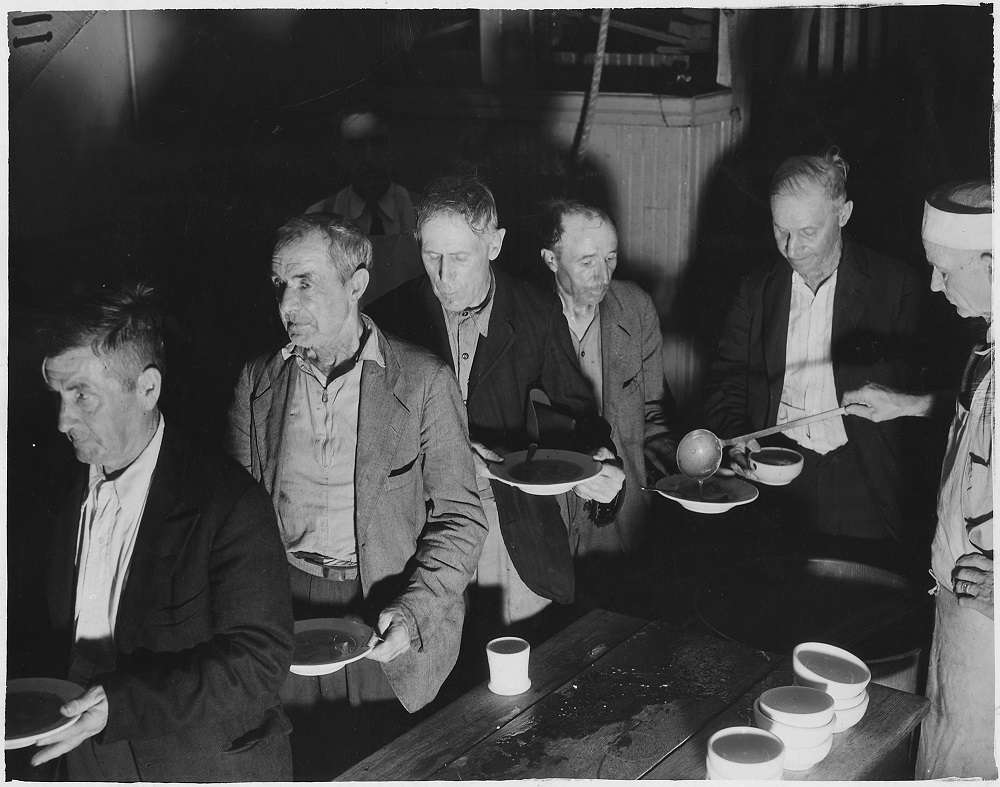

A volunteer serves free soup to a line of men in 1936. National Archives Identifier 196174.

From the youngest ages, Schwartz followed her creative impulse, turning the materials from her household into artistic media: drawing with sticks in dirt; sculpting with bread dough; and drawing on the walls of the family house. Her creative and expressive pursuits, along with those of her siblings, were especially encouraged by her mother. As a result, Schwartz was further exposed to more traditional artistic media—Conté drawing crayons, oil paints, and more—among her sibling’s possessions.

Conté crayons, like those used by Schwartz for her earliest drawings. From Wikimedia Commons, under Creative Commons: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Lillian Schwartz in the 1930s. Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

With her father suffering from heart disease, and in the throes of the Great Depression, Schwartz and her siblings worked from an early age, and moved houses often. She and her family experienced violent anti-Semitism, with her mother often keeping her home from school for fears for her physical safety. While these experiences positioned her as an outsider, her creativity and passion for art were undiminished.

A pro-Nazi rally held in Madison Square Garden in 1939. Department of Defense. Department of the Army. Office of the Chief Signal Officer. (09/18/1947 - 02/28/1964); ARC Identifier 36068 / Local Identifier 111-OF-2 1943, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

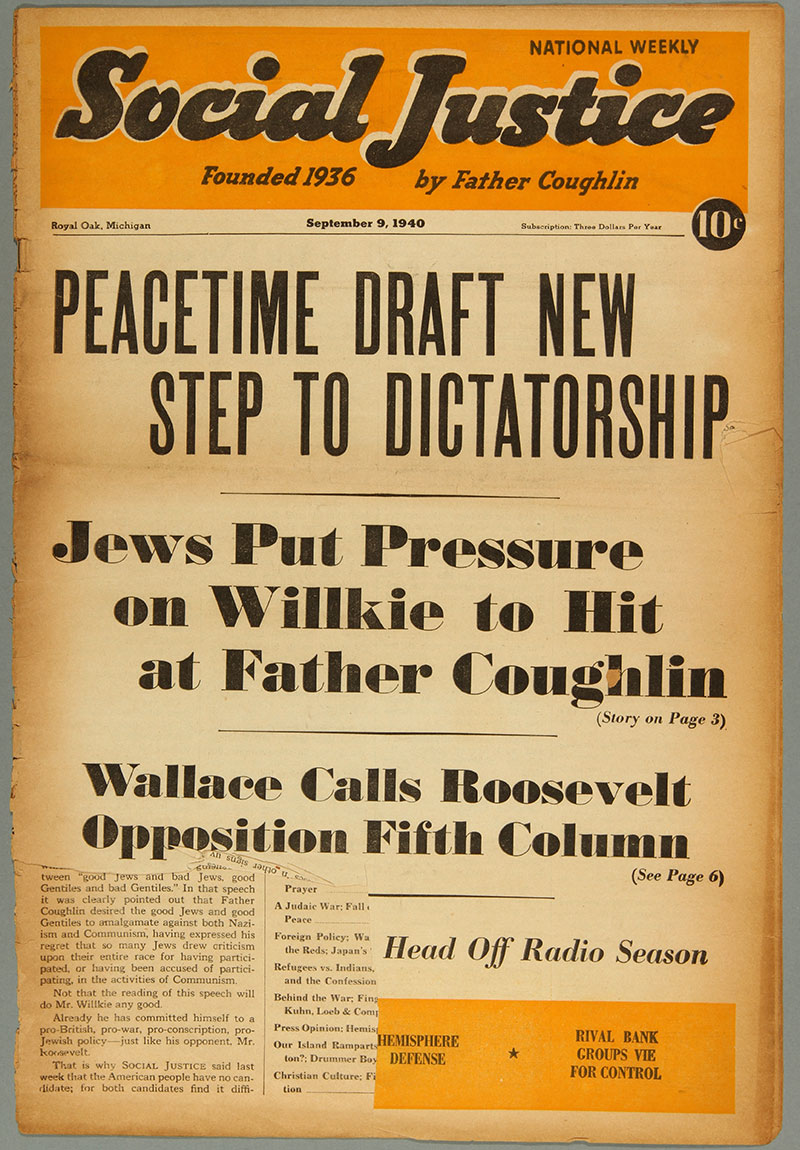

Anti-Semitic publications appeared, and appear, across the United States. This one from 1940 originated in the Midwest, where Lillian Schwartz lived. Collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Poster for the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps. From the collections of the Pritzker Military Museum and Library. Accessed through WikiMedia.

Lillian Schwartz found a way to further her education: the Cadet Nurse Corps, which started in 1943. This federal program addressed the dramatic shortage of nurses by covering almost every cost of nursing school, and explicitly did not discriminate based on race or religion. Cadet nurses were simply required to serve as a nurse for the duration of the war. Schwartz jumped at the chance to pursue her education, joining the Cadet Nurse Corps at the University of Cincinnati. She found nursing difficult, finding herself perhaps too sensitive for it, but reinforcing her identity as an artist. At the University, she also met a young physician who would soon become her husband, Jack.

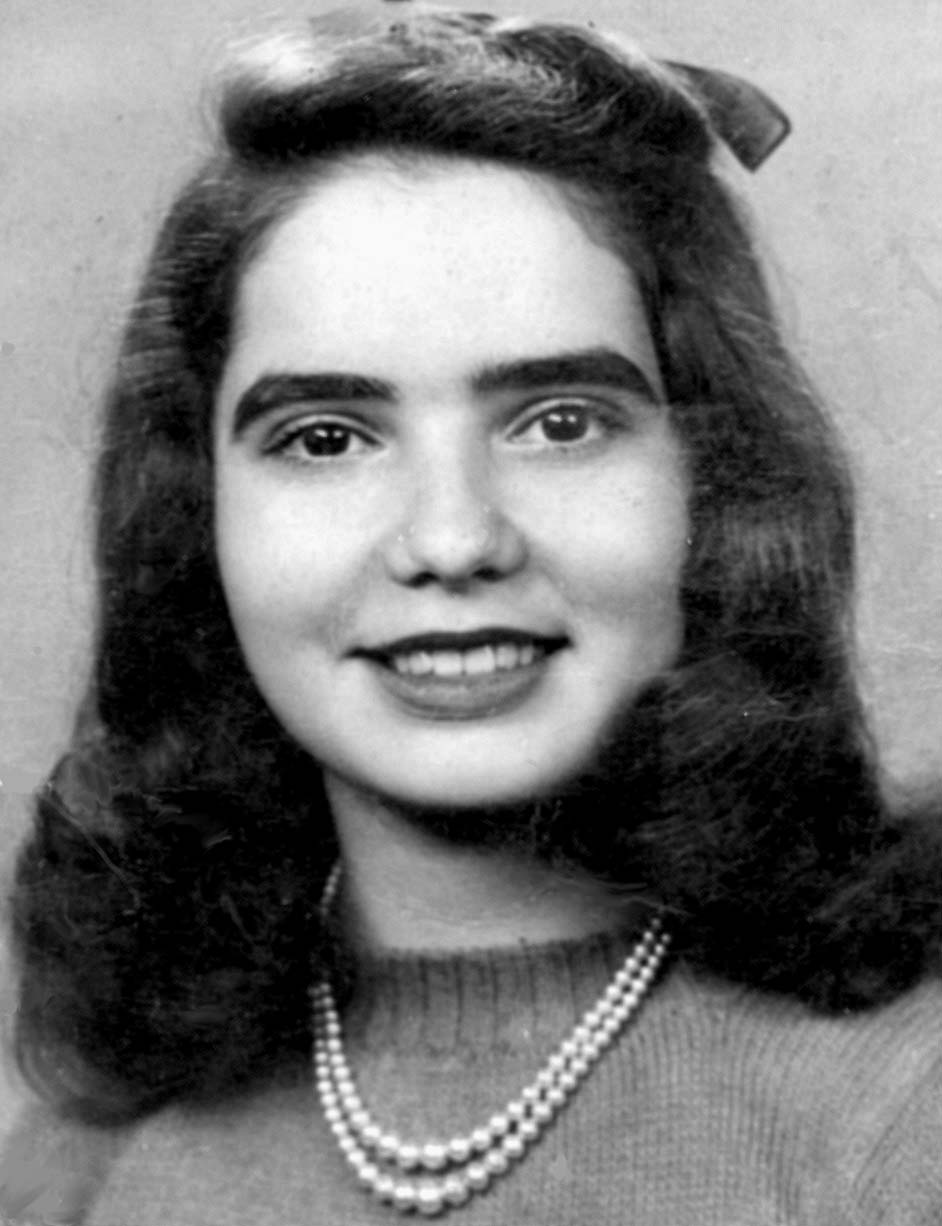

Lillian Schwartz in high school. As high school was ending, Lillian Schwartz’s true desire was to study art at college. Her and her family’s circumstances, however, made that seemingly impossible. Instead, her sister first found her a job as a secretary. Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

After the war, Schwartz accompanied her husband to occupied Japan, where he was completing his service. The couple was based in the port city of Fukuoka, which had been firebombed during the war. With severely damaged infrastructure of all kinds, diseases were a serious challenge. Schwartz began suffering severe neck pain and stiffness and was quickly diagnosed with polio. Paralyzed from the waist down and in her right arm, she became a patient in the hospital in which her husband worked.

A mislabeled photograph of Fukuoka, c. 1950. Note the uniformed U. S. military member to the far right. Collection of Rob Ketcherside, Flickr. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

Lillian Schwartz was not alone in her strenuous efforts to recover from polio. This photograph from 1948 shows a patient in Ann Arbor, Michigan working to recover from polio through physical therapy. From the Ann Arbor District Library.

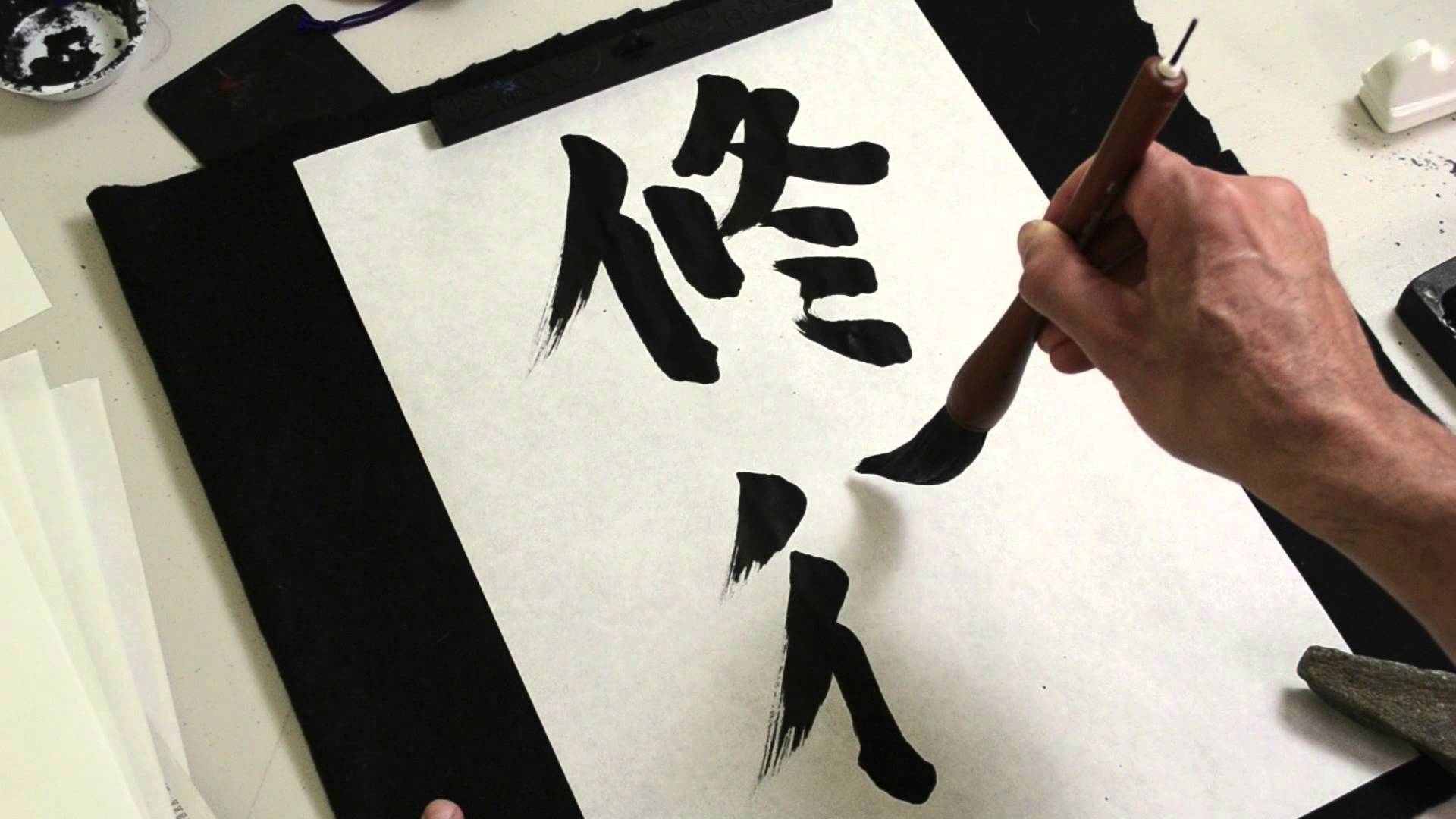

During her long recovery, Schwartz worked with an expert in the art of Japanese calligraphy. With him, she practiced visualizing each motion and brushstroke needed to create the complex forms. This practice of detailed visualization, Schwartz found, greatly expanded her artistic imagination. Recovered, but still living with post-Polio syndrome, she returned to the U.S. with Jack, soon settling their family in northern New Jersey.

An example of the expressive and considered brushwork involved in Japanese calligraphy. Image from Ayu Nabila on Wikimedia Commons. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

As her husband established his pediatric practice, Schwartz dove deeper into her study and practice of art. She studied both oil and watercolor painting, and then began creating sculptures in acrylic. In her painting and sculpture both, she made creative and unusual use of her materials. In her words, she was always “pushing the medium.”

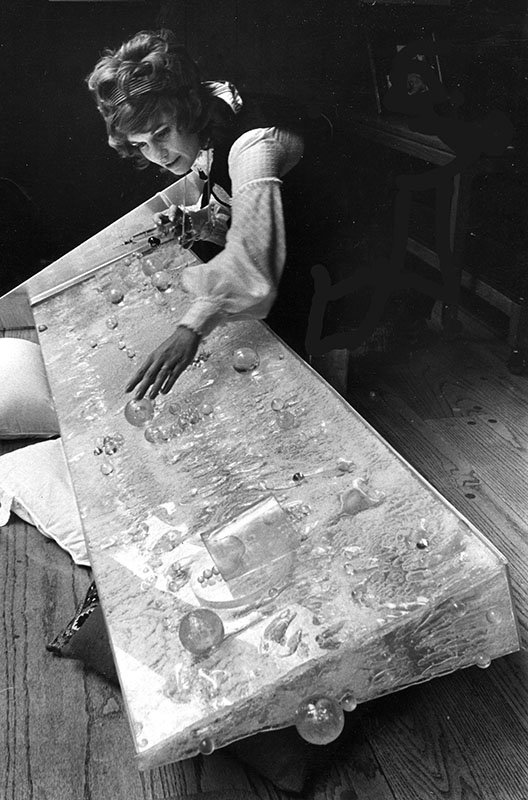

Lillian Schwartz with one of her early acrylic “acrylicast” sculptures. She treated the bulk of the acrylic with solvents and blowtorches to achieve visual transformations, and affixed spheres and other shapes to the surfaces. Often, she presented these sculptures with lighting elements. Courtesy of Lillian and Laurens Schwartz

The New York City skyline, in June 1960. Photographer: Harold Edgeberg. From Wikimedia Commons. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

In the 1960s, New York City figured larger in Lillian Schwartz’s life and art. A short half-hour train ride from her home in New Jersey, Schwartz regularly visited New York’s art museums and galleries, many times bringing her children. On other visits, she collected surplus and abandoned technological materials, transforming them into new artistic media. She created a long series of acrylic sculptures, manipulating the material, shaping it, and adding elements to it. By the mid 1960s, she was creating kinetic sculptures, with colored liquids pumping through glass tubing.

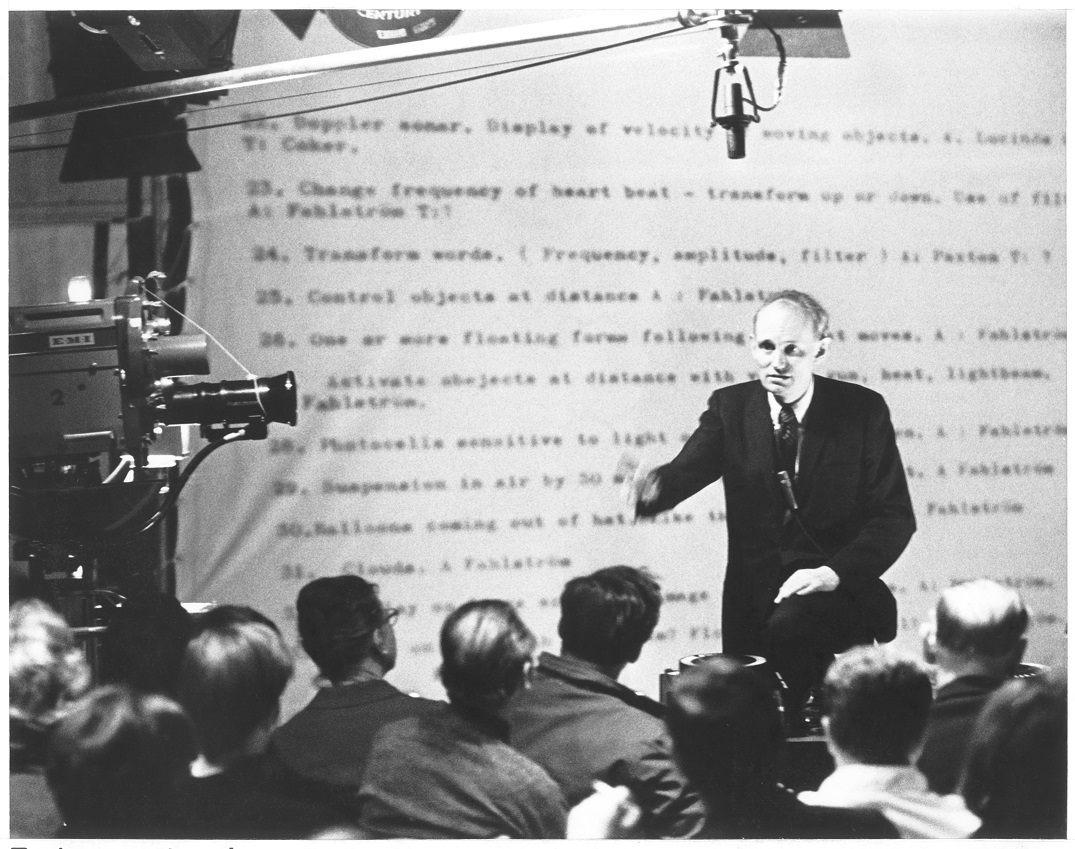

Experiments in Art and Technology, E.A.T., was established in 1967 in New York City. One of the co-founders was the Bell Labs engineer Billy Kluver, who also collaborated with Andy Warhol. Kluver is pictured here lecturing about E.A.T. in 1967. Photographer unknown. Courtesy E.A.T. Archives. All rights reserved.

The other co-founder of E.A.T. was the American painter, Robert Rauschenberg. He is pictured here with one of his works in 1968. From the Dutch National Archives, via Wikimedia Commons.

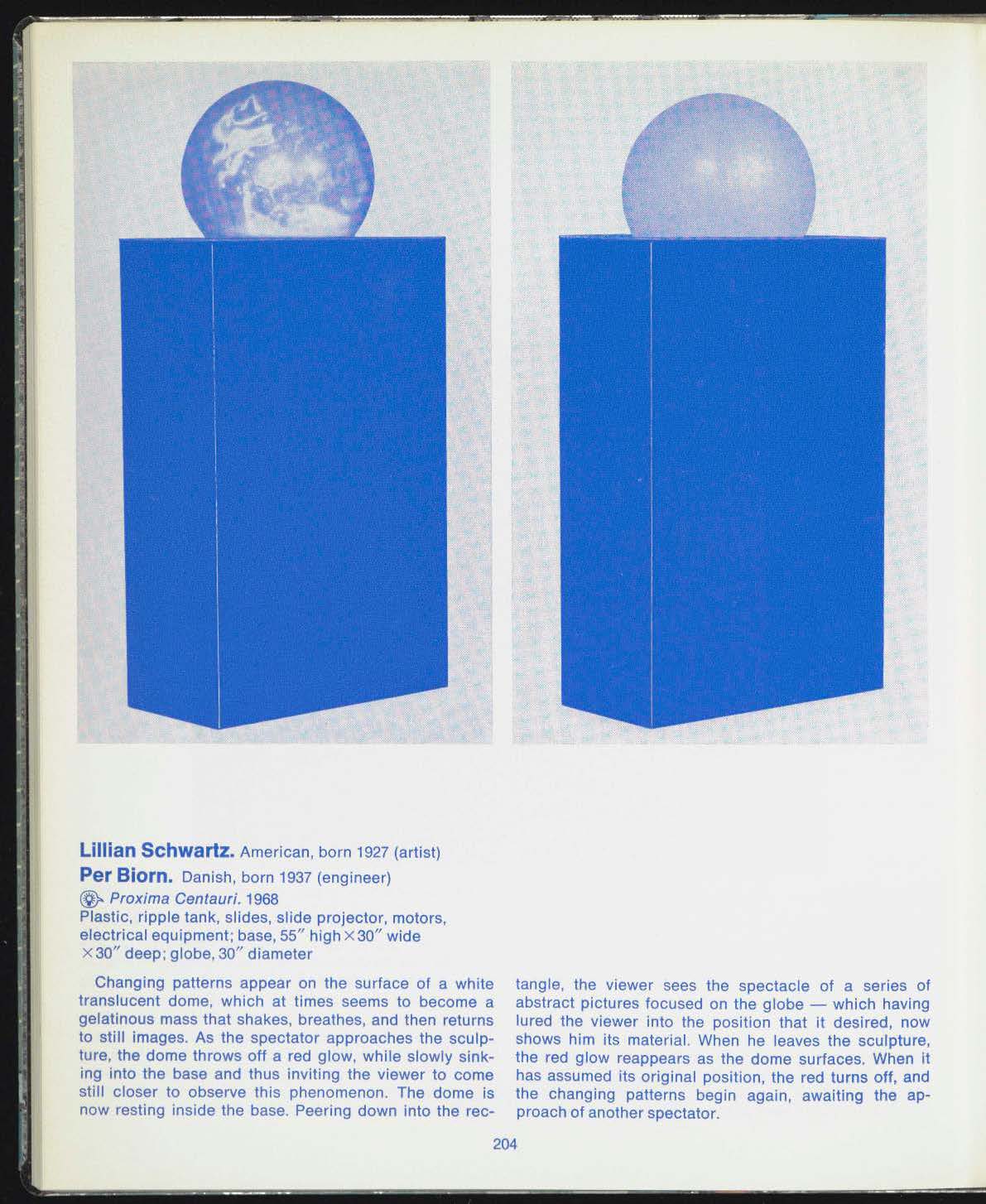

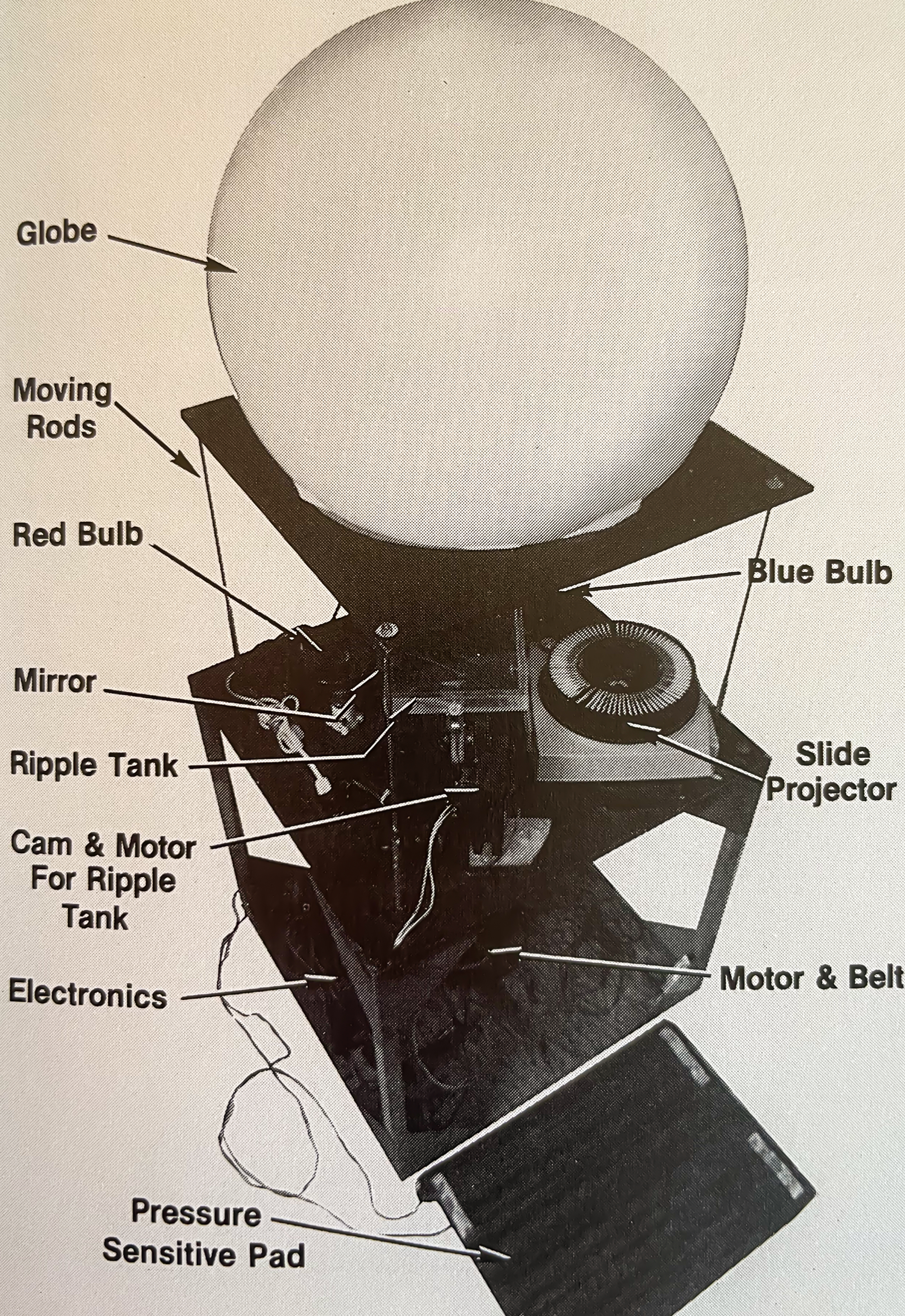

This work brought her into a new development in the New York artworld, a project called E.A.T, Experiments in Art and Technology, led by the painter Robert Rauchenburg and the Bell Labs engineer Billy Kluver. Schwartz attended meetings of the E.A.T. group, which paired engineers with artists to collaborate on new works of art. As part of E.A.T., in the late 1960s she developed a new, complex, multimedia, interactive sculpture, Proxima Centauri. In it, a globe covered by colorful, changing projections responded by retreating into its base when viewers tripped a sensor. The sculpture was included in the exhibit “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Machine Age” at the Museum of Modern Art, along with several other E.A.T. works. The exhibit ran from November 27, 1968 to February 9, 1969.

The entry for Proxima Centauri from the MoMA catalog for the “Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age.” Per Biorn was a Bell Labs engineer who was paired with Lillian Schwartz to collaborate with her on the sculpture. From the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

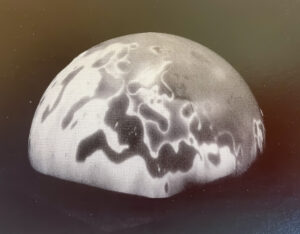

View of the “Proxima Centauri” globe, and a description of the sculpture’s technology. Courtesy Lillian and Laurens Schwartz.

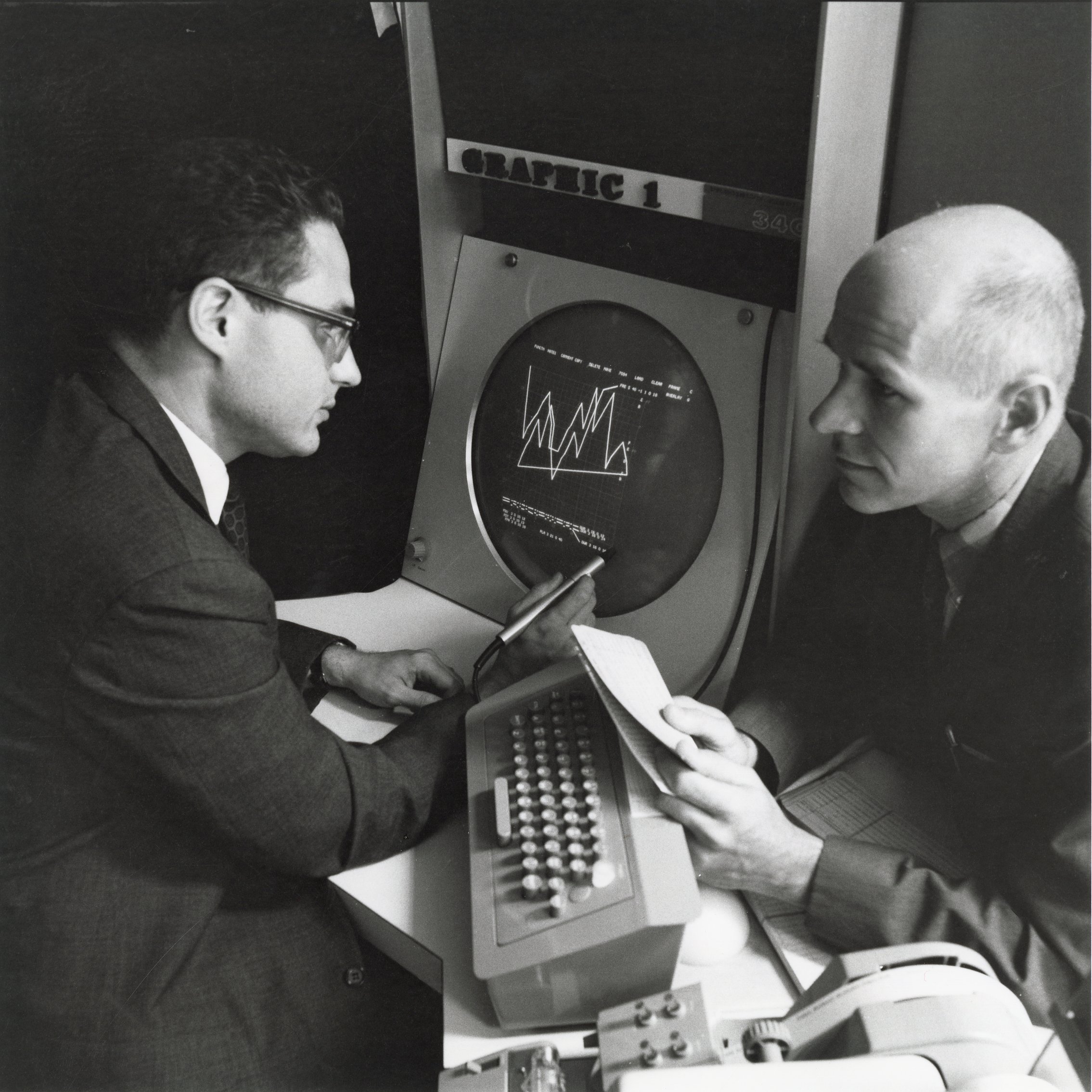

Ken Knowlton (left) and Leon Harmon (right) with their computer-generated print, “Studies in Perception.” Courtesy of the AT&T Archives and History Center.

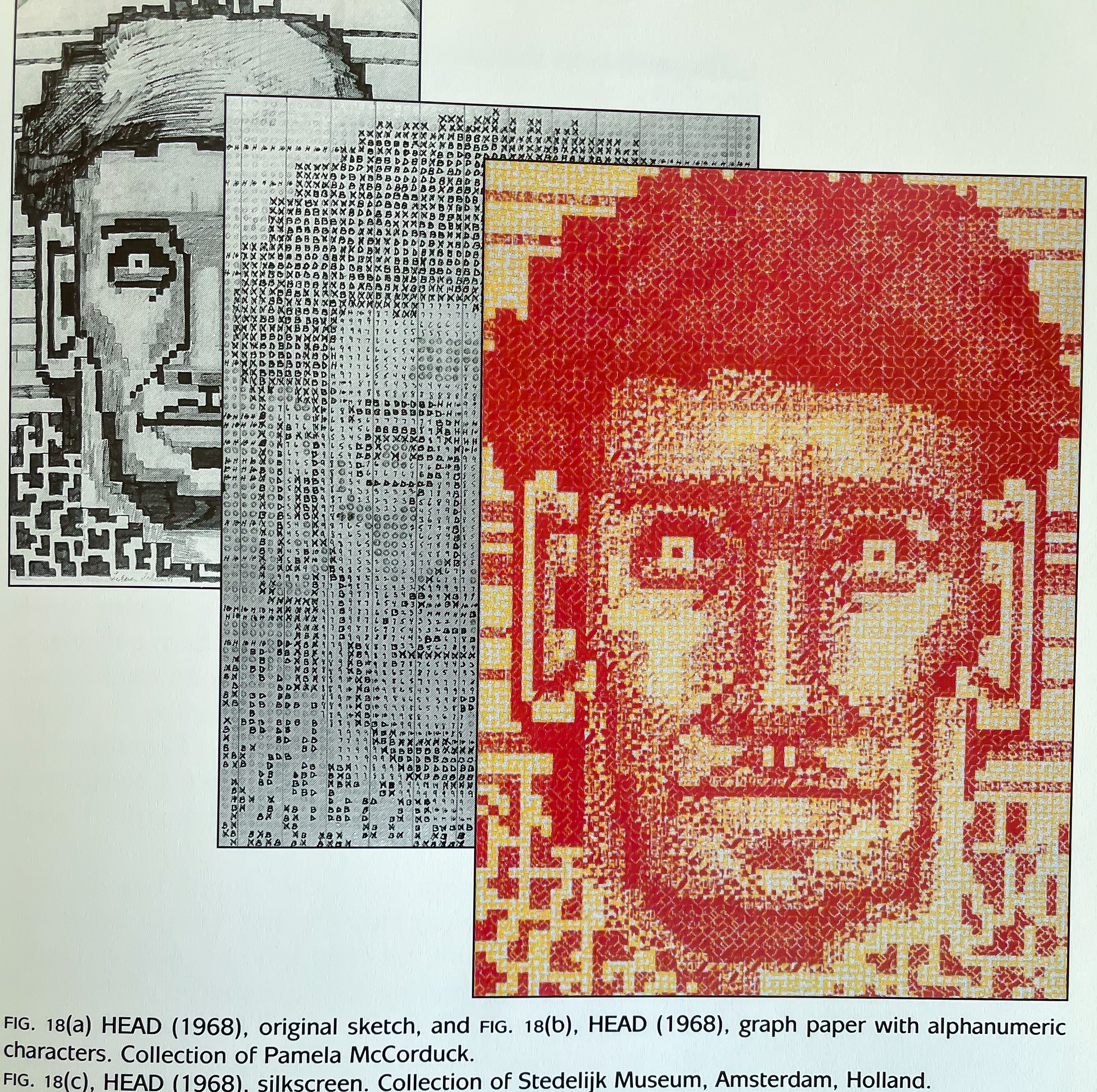

Lillian Schwartz’s invitation to Bell Labs grew into a decades-long residency. She was quickly enthralled by the computer, and was assisted by several computer professionals to explore how she might use it to create art. Her first work with the computer was a print titled “Head,” formed much like “Studies in Perception.” However, Schwartz characteristically decided to push this new medium, transforming the image through subsequent silk-screen printing.

The silkscreened image, “Head,” created by Schwartz when she first came to Bell Labs. At upper left is her original sketch. In the middle is a sketch on graph paper, translating her original sketch into alphanumeric characters. The final silkscreen is based on a computer printout of these alphanumeric characters. From Lillian and Laurens Schwartz’s book, The Computer Artist’s Handbook (W. W. Norton), 1992.

Her focus soon shifted to the very new technology of computer animation, interacting with computer researcher Ken Knowlton. Knowlton had developed a programming language, BEFLIX, used at Bell Labs to generate computer animations. Schwartz took short animations generated at her direction, manipulated them in various ways, and combined them with other imagery and techniques to create a series of short films, moving computer animations into the artworld. Her earliest efforts led to official AT&T sponsorship, and her films from the first half of the 1970s incorporating computer animations garnered both acclaim and wide showings.

Lillian Schwartz in her studio, where she transformed and incorporated the computer animations generated at Bell Labs into her final art films. For them, she intermixed the computer animations with other found footage from the Labs as well as new sequences that she created using various media. Courtesy Lillian and Laurens Schwartz.

A selection from Lillian Schwartz’s 1970 film, “Pixillation.” Moving Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

A selection from Lillian Schwartz’s 1971 film, “UFOs.” Moving Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

A selection from Lillian Schwartz’s 1971 film, “Olympiad.” Moving Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

A selection from Lillian Schwartz’s 1972 film, “Mutations.” Moving Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

A selection from Lillian Schwartz’s 1972 film, “Googolplex.” Moving Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

A selection from Lillian Schwartz’s 1974 film, “Metamorphosis.” Moving Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

In this same period, Schwartz engaged with another emergent electronic medium, video, to produce video art. She drew on the resources of the TV Lab at the television station WNET/Thirteen in New York City, where Nam June Paik and others had developed pioneering video art and video art tools.

A selection from Lillian Schwartz’s 1977 video piece, “Trois Visage.” Moving Image from the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Lillian Schwartz at work at Bell Labs in the 1970s. Courtesy of Lillian and Laurens Schwartz.

Through the support of electronic music pioneer Max Mathews, a high-ranking researcher at Bell Labs, Schwartz received official status at Bell Labs, continuing her use of computers for artmaking and her interactions with scientists and engineers for several decades.

Max Mathews (right) with Lawrence Rosler, in a 1966 exploration of a graphical language for generating computer music at Bell Labs. Courtesy of AT&T Archives and History Center.

She pursued other important collaborations as well, with IBM and particularly with the MIT Media Lab in the use of Symbolics artificial intelligence computers for artmaking. In these collaborations, and on her own primarily using Apple Macintosh computers, Schwartz continued to push the boundaries of the computer as an artists’ tool, and to educate others in its use. In continuation of her work both with computers and with video, she won an Emmy award for a public-service advertisement for the Museum of Modern Art, promoting their 1984 reopening.

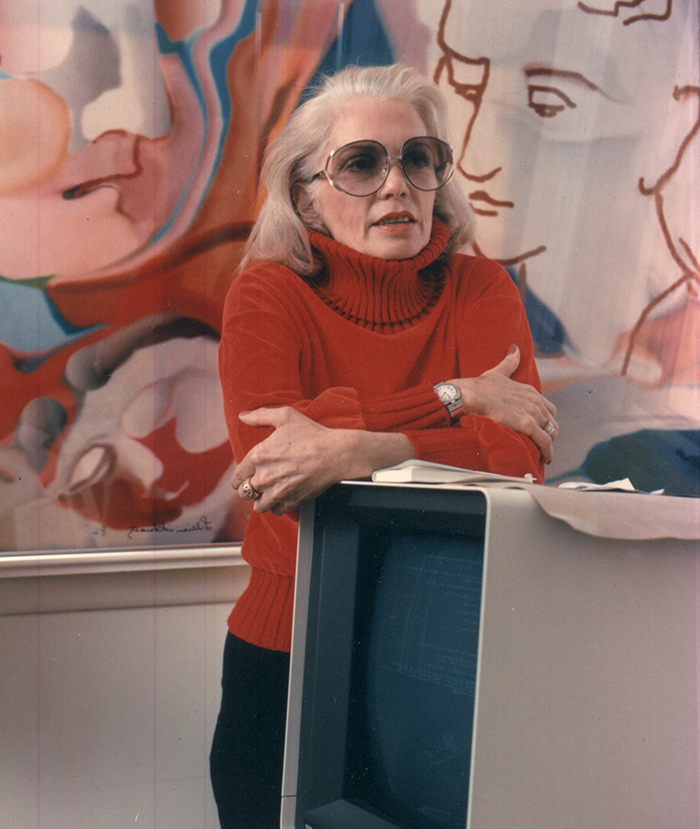

Lillian Schwartz c. 1980s. Courtesy Lillian and Laurens Schwartz.

While vision challenges prevent her direct use of the computer today, Schwartz continues to make art, creating a series of drawings that she intends to animate using the computer.

Lillian Schwartz at work in her New York City apartment, August 2021. Photograph by Matthew Cavenaugh.

Her body of work—both her computer films and video art—were important steps in the emergence of time-based media art in the artworld, opening fresh avenues in both the history of computing and the history of art.

Lillian Schwartz with her CHM Fellows award, August 2021. Photo by Matthew Cavenaugh.

Lillian Schwartz with her CHM Fellows award, and with her son Laurens Schwartz, in her New York City apartment, August 2021. Photo by Matthew Cavenaugh.