SRI's packet radio research van, from which internet protocols were demonstrated.

Over the shortening fall days of 1977, an unmarked silver step van filled with futuristic equipment, shaggy-haired engineers, and sometimes fully uniformed generals quietly cruised the streets of the San Francisco Peninsula. Only an oddly shaped antenna gave a hint of its purpose.

The van was getting ready to demonstrate the first full transmission with what would become the internet standard we use today for nearly everything, from dating to rides to medical information.

“Where the Internet Was Born,” produced by the Computer History Museum.

While some people trace the internet’s origins to the ARPANET network of the late 1960s, the word internet in fact means joining different kinds of individual networks together. The first experiments with such “networks of networks” came around 1973, with the European Informatics Network (EIN) and the trials that led to the PUP standard at Xerox PARC.

By that time the US Advanced Research Projects Agency, ARPA, had started developing a mobile radio network and a satellite network for military use. If it didn’t figure out a way to connect them to each other, and to its original ARPANET, it would be in the crazy position of running three incompatible networks!

Two ARPANET alumni holed up in a Palo Alto motel room for a frenzied weekend and wrote a draft internetworking standard to bridge the gaps. Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf named it TCP (Transport Control Protocol). Kahn would go on to head ARPA’s computing division, and Cerf would join him.

Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf on the 1977 internet demonstration.

The draft went through a number of revisions, at first with the collaboration of the PUP researchers at Xerox PARC and especially the Europeans behind the earlier EIN internetworking experiments. These included researchers from Louis Pouzin’s French CYCLADES network as well as from the NPL Mark I network developed by English networking pioneer Donald Davies.

For a while it looked like there might be a single international standard. But then Cerf and Kahn decided to split off TCP on its own, though still drawing on many features from the international collaboration.

Meanwhile, ARPA’s two military networks had gone from concept to reality. Irwin Jacobs, co-founder of Linkabit of San Diego (which developed into Qualcomm) led the Satellite Network effort, making use of an Intelsat communications satellite to beam data to Europe and beyond.

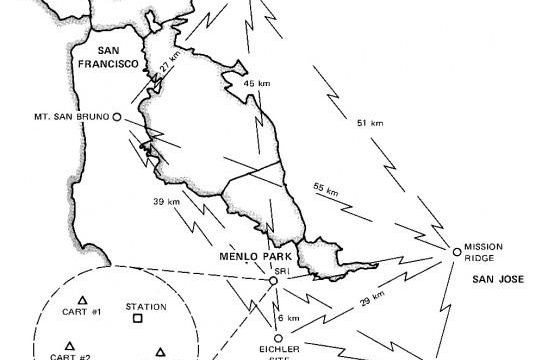

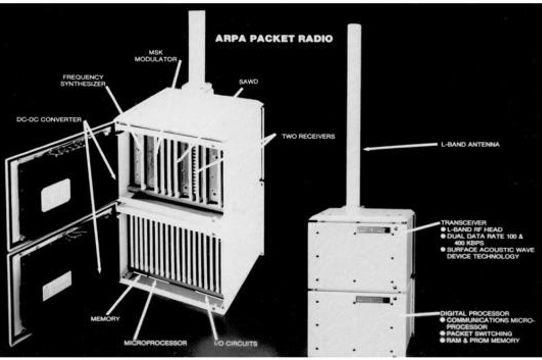

SRI’s Don Nielson led the Packet Radio Network effort, centered around a research van they had specially outfitted as a mobile network node. Collins Radio built special equipment; original ARPANET contractor Bolt, Beranek, and Newman (BBN) developed server software among other tasks.

The Packet Radio network was the ancestor of all the wireless networks we use today, from mobile phones to Wi-Fi.

2007: Panel commemorating 30th anniversary of internet protocols.

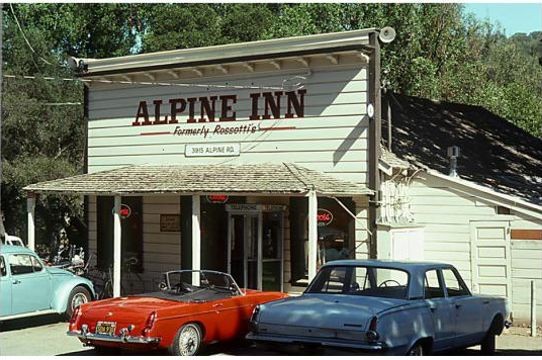

By the August 1976, the teams were ready to try connecting across two networks as a first step. As they sat in the beer garden of biker hangout Rossotti’s, the Packet Radio group successfully sent their weekly progress report through the van over their radio network and then through the ARPANET.

It was a promising start. But while connecting two networks together had been done before could be done with a bunch of one-off hacks, translating data seamlessly across three or more networks would demonstrate unequivocally that TCP was a general internetworking standard.

The preparations took almost another year, and involved groups in multiple US states and four countries.

Virginia Travers (neé Strazisar) of BBN had written the first gateway software for TCP, ancestor of the code inside Cisco and Juniper routers that power today’s net. Like a Johnny Appleseed of internetworking, she spent months traveling to US and European sites to install the software at the points that would be needed for the big test.

Birth of the Internet: Barbara Denny, Paal Spilling, and Virginia Strazisar Travers.

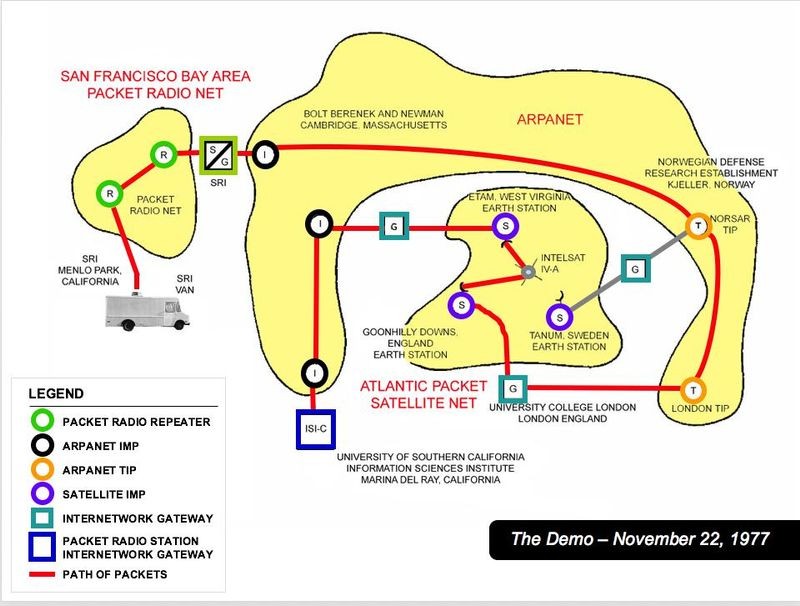

On a rainy Wednesday, November 22, 1977, all was ready. Data flowed seamlessly from the van to SRI in Menlo Park and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles via England, Boston, and Sweden across three types of networks: packet radio, the satellite network, and the ARPANET. All as the van cruised Bay Area roads. The internet was born. Sort of...

Around the world: Path of test packets on November 22, 1977.

It would be six years before ARPA’s internet protocol—now renamed TCP/IP to reflect some additional functionality—was ready to officially install on all of the agency’s networks.

It would be 15 years before TCP/IP defeated powerful rivals to become the dominant internetworking standard world-wide, paving the way for a unified online system like the Web. Along the way TCP/IP beat out powerful corporate standards like DECNET and IBM’s SNA, and most importantly OSI, the official international standard which grew out of the early European internetworking efforts. Al Gore played several roles.

But it all started in the van.

Ten years ago, Don Nielson of SRI and I organized a major commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the 1977 experiment with help from Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn—the program is here and the press release is here. We had a public evening panel, and two days of interviewing all the original participants who came from several parts of the USA and Europe for the occasion.

Today, the SRI Packet Radio van is a part of the Computer History Museum’s permanent collection. A cutaway 3-D−printed model of the van is in the Networking gallery of the permanent Revolution exhibition, made by the same shop at SRI that outfitted the original.

The packet radio van might have looked lonely as it cruised Bay Area streets in November of 1977. But it was part of a carefully planned international effort involving more more than 35 people and eight institutions. The figure below shows the path taken by the test packets.

There were other crucial people and institutions not shown on the map: ARPA, which ordered and funded it all; Collins Radio, which built the packet radios themselves, Linkabit, which developed the Satellite Network; and more listed below.

The following people are among those who helped make the 1977 demo possible:

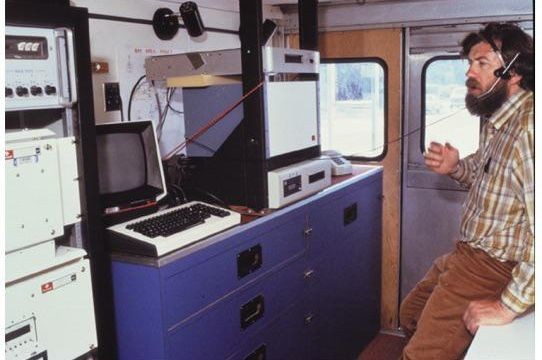

Van interior, looking toward right rear corner. Earl Craighill is standing.

Van interior, looking toward right front corner. Jan Edl of SRI is conducting tests of mobile packet voice, an early form of Skype-like voice over IP (VOIP). The Mickey Mouse phone shows that packet voice works over consumer phones and doesn’t require special equipment.

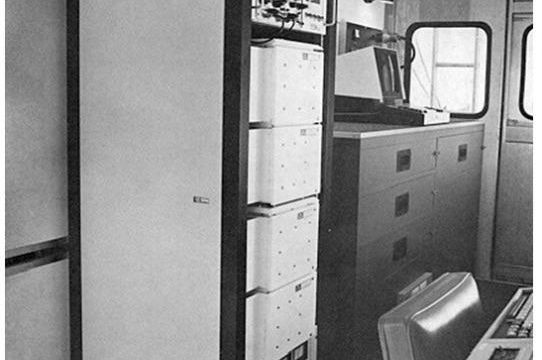

Van interior looking forward.

Packet radio equipment in racks; van interior looking backward.

Map of experimental Packet Radio Network, San Francisco Bay Area.

1976 two-network test, from Rossotti’s/Alpine Inn beer garden. Pictured left to right: Cone, visitor, Geannacopolus, Retz, Kunzelman, McClurg, Mathis.

Rossotti’s/Alpine Inn

Entering Packet Radio weekly report, Geannacopolus

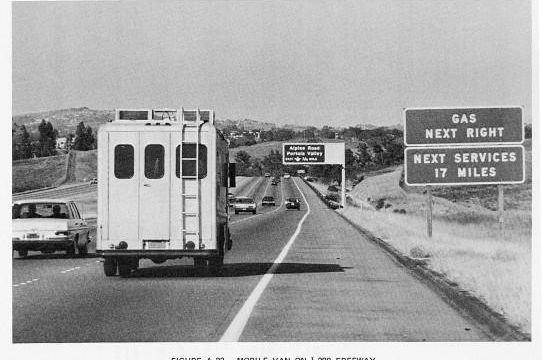

Driving into the future. 280 freeway near Menlo Park.

Vint Cerf (in suit) with Army brass.

Collins Radio Corporation’s Packet Radio equipment.

The van at a Bay Area Packet Radio site.